Time under tension (TUT) is one of those terms that shows up in training programs, social media posts, and gym floor conversations. It usually refers to the total number of seconds a muscle spends contracting in a set. You will often read that hypertrophy occurs best if each set lasts 40 to 70 seconds, or that slowing every eccentric phase builds more muscle. It sounds precise, but it is misleading. TUT is an outcome of how you train, not a primary driver of adaptation. The stimulus that matters is mechanical tension, the force experienced by the muscle fibres when they contract under load.

“Mechanical tension appears to be the primary stimulus for muscle hypertrophy.” (Schoenfeld, 2010)

Where the TUT Idea Came From

The idea of tracking time under tension came from a genuine effort to make training stress measurable. Coaches and practitioners wanted a simple way to explain how hard a set should feel. Counting seconds looked neat and easy to teach: if a set lasts longer, it must be harder. That approach was built on good intentions, not a desire to mislead. But exercise science evolves. As research methods and statistical analysis improve, we become better at separating correlation from causation and refining ideas that once seemed sound.

Mechanical tension depends on how much force a muscle produces and for how long it sustains that force near its capacity. You can extend set time by moving very slowly with light weight, but mechanical tension may be low. Conversely, heavier loads taken close to fatigue can generate very high mechanical tension in a shorter time.

“Time under tension does not independently predict hypertrophy when load and effort are matched.” (Morton et al., 2016)

Understanding Mechanical Tension

Mechanical tension is created when a muscle generates force while it lengthens (eccentric), holds (isometric), or shortens (concentric). The key is combining enough load with enough effort to recruit and fatigue high-threshold motor units. Tempo is not a primary driver of this stimulus; it is a by product of the load you choose and how you control it.

Mechanical tension can be active when fibres contract or passive when they are stretched under load. It is generally maximised when a muscle is in its lengthened position and working against resistance. Current research shows muscles respond strongly when loaded at long lengths, even without deliberately slowing each repetition. The important factor is that the tissue experiences meaningful force for enough repetitions close to fatigue.

“Hypertrophic adaptations are driven by fibre recruitment and mechanical loading at sufficient intensity rather than prescribed movement speed.” (Schoenfeld et al., 2016)

For more on this, see my article on mechanical tension

Why Prescribing TUT Often Backfires

When training is built around an arbitrary time target rather than appropriate load and effort, several things tend to happen:

- Loads become too light to challenge the tissue

- People slow down to hit a clock target, changing movement mechanics

- Focus shifts away from safe, strong execution toward counting seconds

Progressive overload, sufficient effort, and using joint and muscle mechanics to place the target tissue under meaningful tension are what drive change. For example, a lifter who uses very light weight so they can lower for four seconds and lift for four seconds may achieve a long set duration but very little true mechanical tension. They would make more progress using a load that challenges them within their chosen rep range, moving under control but not artificially slow.

Most controlled studies comparing fast and moderate tempos show little difference in growth or strength if sets are taken close to failure. The key is to apply enough load and work hard enough to stimulate adaptation, not to chase a stopwatch.

“When training to volitional failure, tempo and set duration have little impact on strength and size outcomes.” (Wernbom et al., 2007)

Injury Risk and Real-World Performance

When new clients arrive, they often have been told to keep every repetition slow and to aim for a set time under tension. The intention behind this advice is usually well intended, and often states safety or muscle activation, but the effect can be the opposite. Very slow tempos with insufficient load can alter mechanics and irritate joints. They also limit the stimulus needed to reach aesthetic or performance goals.

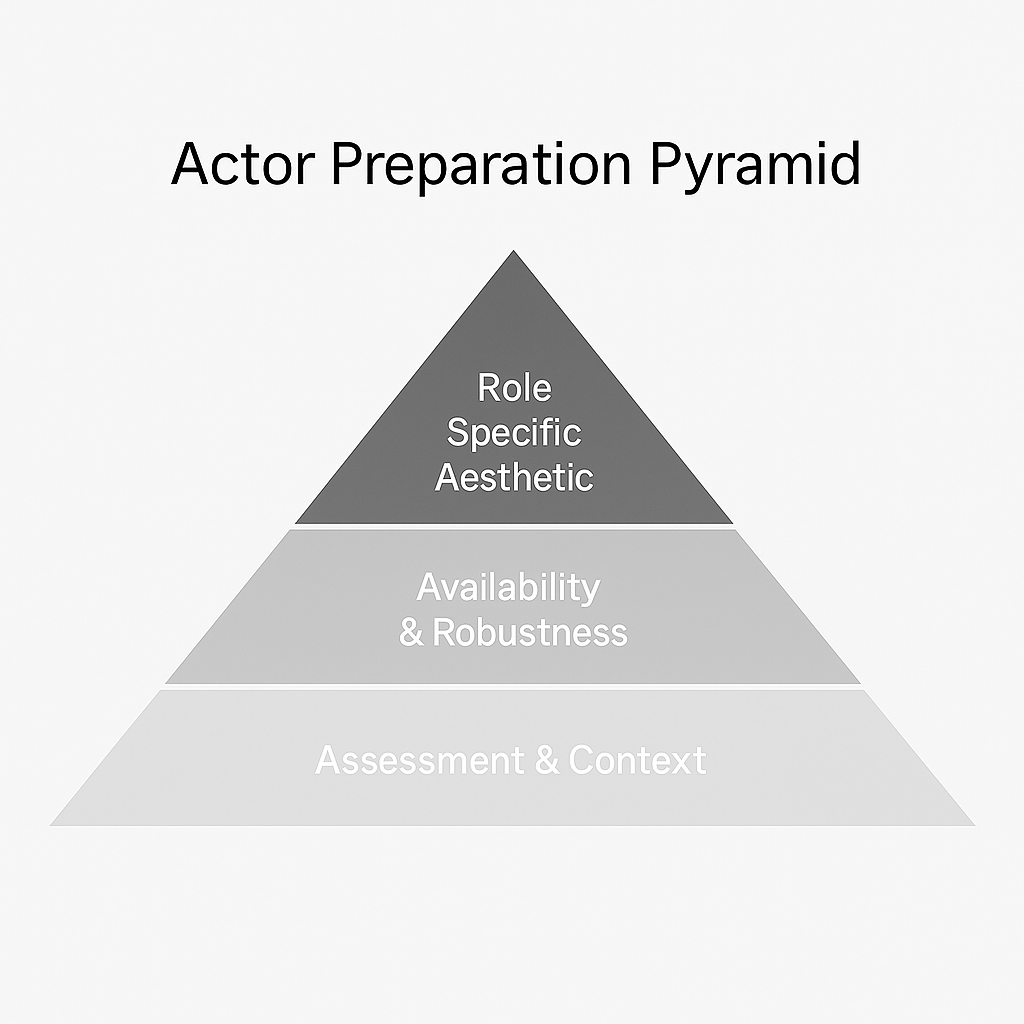

In film preparation, consistency is essential. Actors have to be physically ready on a fixed date. Counting seconds does not add protection. Technical control, appropriate load, and progressive overload do. If injury interrupts training, visual readiness and movement quality can suffer and production timelines can be affected.

Practical Guidance

- Select a rep range that fits your goal

- Apply effort and intent: each rep should be purposeful and effortful, with the goal of producing meaningful force

- Technique and mechanics should be optimised so the target muscle experiences maximum tension throughout the movement

- Work close to technical failure. This is the point where movement quality begins to break down. Rather than the point at which you can no longer move the weight.

- Progress gradually by increasing load or total work as strength and skill improve

- Accept that tempo will vary slightly between individuals and exercises; what matters is maintaining control to reduce injury risk

Effort, intent and appropriate mechanics to maximise mechanical tension are what drive progress. A hard set of eight reps might last twenty seconds and a hard set of twelve might last thirty-five. Both can build muscle and strength if the reps are performed with focus and sufficient mechanical tension.

“The hypertrophic response is similar across a wide range of repetition durations when sets are taken close to failure.” (American College of Sports Medicine, 2009)

FAQs

Is time under tension useless?

Not exactly. It shows how a set was performed but does not drive adaptation on its own. Mechanical tension and effort are what matter.

Should I slow down reps?

Only enough to stay controlled and reduce injury risk. Extremely slow speeds do not lead to more growth or strength.

What about eccentric training?

Lengthening contractions are useful because they create high mechanical tension at long muscle lengths, not because of extra seconds.

Does time under tension matter for beginners?

Beginners benefit more from learning control and technique than chasing a set duration. Focus on good movement patterns, effort, and intention.

Does tempo matter in strength training?

Tempo only matters in the sense that you should move with control. There is no single speed that leads to more growth or strength once sets are taken close to technical failure. Focus on purposeful movement and tension rather than fixed counts.

For actors or performers?

Prioritise consistent training that builds strength and the required look while protecting availability. Use movement assessment and exercise selection to create maximum tension safely rather than counting seconds.

References

Schoenfeld BJ. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2857-2872.

Morton RW, et al. Neither load nor systemic hormones determine resistance training-mediated hypertrophy or strength gains. J Appl Physiol. 2016;121(1):129-138.

Wernbom M, Augustsson J, Thomeé R. The influence of frequency, intensity, volume and mode of strength training on whole muscle cross-sectional area in humans. Sports Med. 2007;37(3):225-264.

Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(11):1689-1697.

American College of Sports Medicine. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687-708.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.